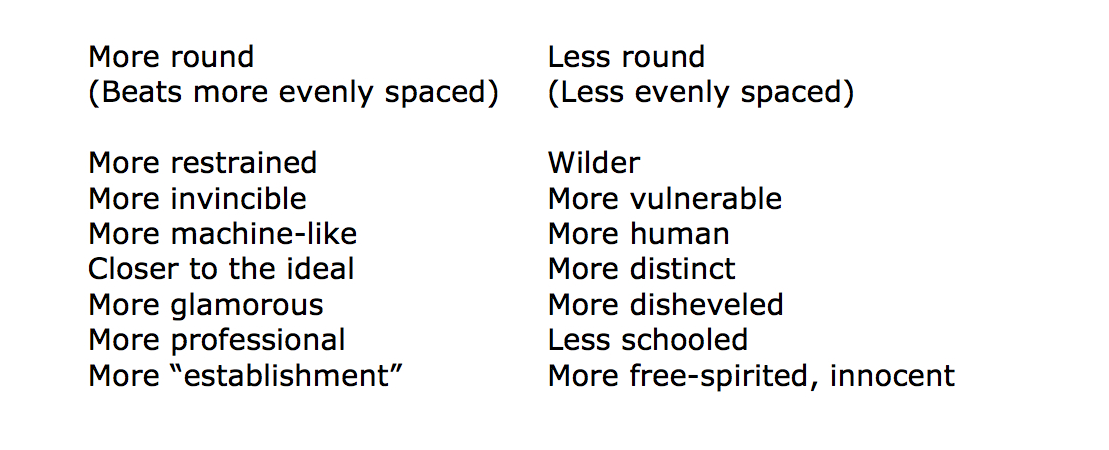

When non-musicians ask me who my favorite drummers are, they are surprised to hear me list names such as Earl Young, James Gadson, and Al Jackson, of whom they've never heard, or Charlie Watts and Ringo Starr, familiar names but not regarded by these friends as maestros. None of these drummers are known for their flash. None of them are Buddy Rich, the name some of these friends may have been expecting me to list first. My favorite drummers hide their mastery in plain sight.

When playing with other musicians, most of what drummers do is to play a repeating beat that shapes musical time for the ensemble and gives that time texture. On the surface, it's a simple task, and yet the difference between the average drummer’s backbeat and that of, say, Charlie Watts, is vast. The problem is, it's hard to talk about (which may be one reason why conversations about the best drummers quickly zero in on those with the fastest hands, a more easily grasped concept).

We need to learn how to listen to and talk about feel, which is therefore the very foundation of musical technique, especially for drummers. Drummers who develop their feel not only improve their drumming, they free the musicians around them to better express their ideas. The right feel brings those ideas to life; the wrong feel obstructs them, which is why bands go through so many drummers.

Here is a short introduction to how I hear and think about feel.

I. Hearing the Shape of Time

Understanding feel requires deep listening to recordings of great drumming. This listening will be most useful if you first create some mental images to help you hold on to what you hear.

Let’s start with the idea that musical time can be thought to have shape, a wheel that turns at a rate of once per measure. Thus, the beats of the bar represent points along the edge of the wheel.

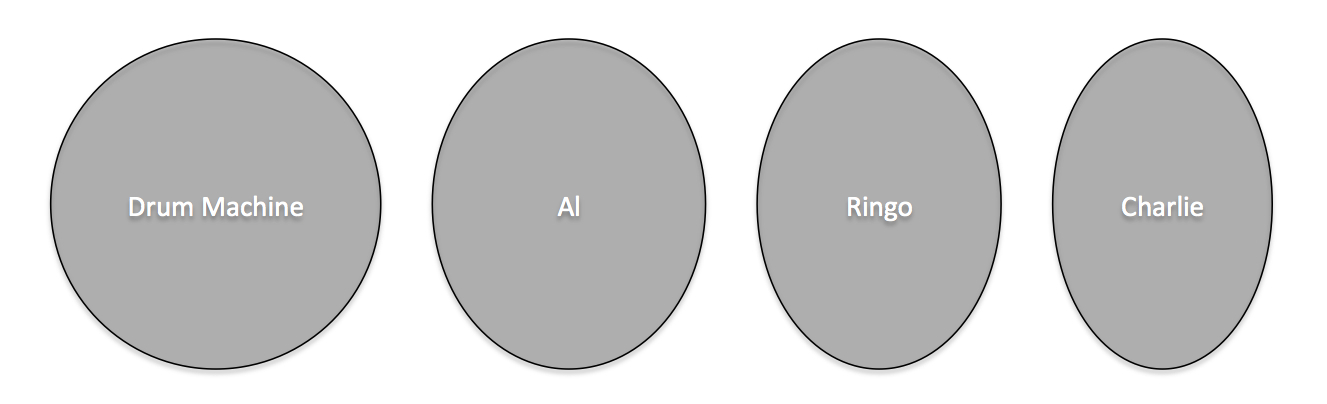

Here’s where it gets interesting. A car wheel is a perfect circle, but the wheel of musical feel is not. Though drum machines and computers can shape musical time as a perfect circle (the beats spaced with exact evenness), we humans, thankfully, are not so mechanical. We space the beats unevenly, laying some beats back and pushing others forward. If you lay back slightly on “two” and “four,” you create the sense of an ovalar wheel, one that labors to get to "two" and "four" but settles more easily into "one" and "three." As you lay the offbeats further back, you elongate that oval. If you were to skitter about with less regularity, you'd create something more misshaped (which can be cool, too).

You needn’t have a precise grasp of this image to get the gist, which is this: Just as a car with oval wheels would move along with a certain kind of bounce, music gains a certain lilt, bounce, or shakiness depending on how the drummer shapes the wheel of musical time, again according to the spacing of the beats in the bar. Whether nearly circular, elongated, or chaotically jagged, each shape has its virtues. Sometimes a jagged wheel is best! Though the shaping of this wheel is done unconsciously, how the drummer shapes the wheel has a decisive impact on what musical ideas the other musicians express and the mood attained by the listeners. As you listen to the following examples, see if you can hear how the playing of simple drumbeats establishes the musical mood.

Three Examples

Let’s briefly compare the feels on three tracks: Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together,” the Rolling Stones’ “Tumbling Dice,” and the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends.” How do these three great drummers—Al Jackson, Charlie Watts, and Ringo Starr— bring these songs to life?