John Masefield. Image via poetryfoundation.org.

The Oblique Strategies are the creation of musician Brian Eno and artist Peter Schmidt. The strategies are a collection of statements, commands, principles, and questions designed to help artists break through creative logjams.

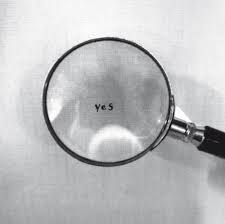

They originally existed as a deck of cards, so an artist working on a project could, if stuck, reach for the deck, draw a card, and act upon what the card offered.

Examples include . . .

Reverse.

Use an old idea.

State the problem in words as clearly as possible.

Only one element of each kind.

Cascades.

What would your closest friend do?

What to increase? What to reduce?

Are there sections? Consider transitions.

Try faking it!

Ask your body.

Work at a different speed.

One of the cards has particular relevance to roughness: “Honour thy error as a hidden intention.”

Consider the case of “Sea Fever,” a poem by John Masefield. The opening line may well have been written . . .

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky

But in various versions, the line appears . . .

I must down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky

This may have been the result of a printing error. Here is a proof of an early printing.

But later printings restore "go down," as Masefield himself reads the poem in this recording.

Some people know this poem in the first version, and others know it in the second. Whichever version one prefers, one can hear that the strangeness of the mistake takes on intention and mystery

“I must down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky.”

Thank you for reading.