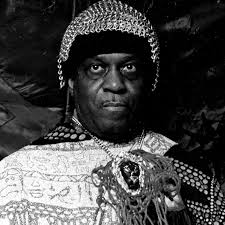

Nina Simone. Image via jazzinphoto.wordpress.com.

At the beginning of this recording of “I Shall Be Released,” Nina Simone can be heard stopping the band and exhorting them not to push. The false start and the brief correction she gives to the musicians were preserved as part of the recording.

All of that might have been cut, but its inclusion provides a window into the making of the song and the difficulties of recording and performing. Simone’s dialogue enlivens the recording not only because it’s interesting to hear a performer at work in the studio, but also because we then listen to the song knowing that the question of not pushing is in the minds of the musicians. Even as the song progresses and we let go of that concern, the rough and tumble moment at the start has infused the performance with a little more life.

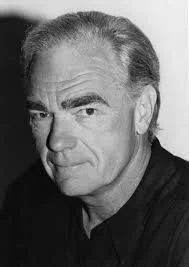

Simone in the studio. Image via ninasimone.com.

We have heard something more like the whole truth of the recording, and it feels more alive as a result.

Thank you for reading.