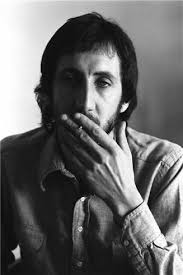

Pete Townshend. Image via www.morrisonhotelgallery.com.

One tradeoff that many artists make unconsciously is to take steps to seize control. This might take the form of acquiring of special equipment that allows greater control over materials—a fancier loom, a synthesizer with more knobs, a digital audio rig, and so forth.

Another form of taking control comes by way of personnel changes. Musicians, for example, often go solo to make the record that their band mates had resisted. By striking out on her own, the leader has gained control. She can pick and chose players who will carry out her ideas more competently and just as she requests. No more resistance or squabbles—it’s a dream.

Yet the lack of resistance and improvement in competence are not pure gain. What about the sense of difficulty and fight that may characterize the band’s performances?

Consider, for instance, some of the differences between . . .

“Going Mobile,” from Who’s Next by The Who.

and . . .

“Secondhand Love,” from Pete Townshend’s solo album White City: A Novel.

Townshend wrote and sings both songs. One needn’t declare a preference in order to appreciate the tradeoffs inherent in recording as a member of a band versus recording as a solo artist.

The groove of “Secondhand Love” is not only more polished, it breathes with the air of deference captured on solo records. “Going Mobile,” by contrast, is more contentious. Note, for instance, how Keith Moon’s drum part and John Entwistle’s bassline speak of players in competition for the audience’s ear. No element in “Secondhand Love,” beyond Townshend’s voice and guitar, makes such an overt bid for our attention.

Players on a solo record aim to carry out the singular vision of the artist, whereas band mates exist in an ongoing contest for attention. That competition is what charges band performances; it can also drive a singer/songwriter crazy.

Townshend, famously aware of the ensemble around him, surely understood these tradeoffs and got what he wanted from “Secondhand Love.” He also understood what he gave up in the process. How many artists can claim to be so conscious of what they might gain by ceding control?

Thank you for reading.